Heroes and Villains

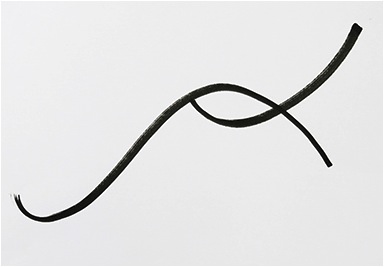

It’s not often that we get to meet our heroes, but courtesy of Bond’s 2016 conference I got to meet one of mine and receive a free signed copy of his most recent book. I first came across Charles Handy when I was starting out in OD consulting back in 1984. At that time there were very few readable books on organisational development so Handy’s Penguin paperback Understanding Organisations came as a breath of fresh air. It was such an enjoyable read I remember taking it on holiday to a cottage in France (yeah, I know – but I did take some novels too!) Since then I have been an avid reader of Handy’s books on organisations and their place in wider society. Charles Handy’s most recent work The Second Curve: Thoughts on Reinventing Society revisits a number of his earlier ideas and places them in a contemporary context. If I remember correctly, Handy introduced the idea of the second curve in 1994 in his book The Age of Paradox. Organisations go through life cycles. Over time they may become increasingly effective but at some point they begin to peak and their effectiveness curve begins to descend. According to Handy, “The descent can be prolonged, and often is, but oblivion waits at the end.” However, descent doesn’t have to be inevitable providing the organisation can find a new sense of purpose and ways or working – the ‘Second Curve’. “The nasty and often fatal snag is that the Second Curve has to start before the first curve peaks. Only then are there enough resources – of money, time and energy – to cover that first initial dip, the investment period”, as Handy explains. I found the metaphor very enlightening back in the 1990s and it continues to provide a valuable conceptual model in the courses on Organisational Development that I teach.

I found the metaphor very enlightening back in the 1990s and it continues to provide a valuable conceptual model in the courses on Organisational Development that I teach.

In The Second Curve, Handy applies this idea to the workplace, the market, social insurance and education systems, and many other settings. He argues for ‘Second Curve’ alternatives to growth models of development, and the capitalist system on which they are based. I wonder what Handy’s previous employers in the oil giant BP would have to say about that! He examines ideas like disruptive change, the ‘Just Society’ and citizen organisations and puts forward suggestions for re-thinking leadership, organisation structures, and how we as individuals can re-imagine the way we manage our work, careers and the contribution we each can make to society. Many of Handy’s ideas will be familiar to readers – particularly if they know his earlier books – but they are no less stimulating for that and his elegant writing style makes his arguments compelling.

I listened to Charles Handy’s presentation at the Bond conference with rapt attention and read his book on the train back to Scotland. Here was someone drawing on eight decades of wisdom and unafraid to take a critical stance against some of global capitalism’s shibboleths. At times I was struck by how some of his critical analysis of corporations may also apply in the world of NGOs. NGOs may not be immune to all of the criticisms that Handy makes about the “glass towers of capitalism” simply because their ultimate purpose is the pursuit of social change rather than money. The organisational immune systems of NGOs may not be that effective.

Many of Handy’s Second Curve ideas are based on fascinating pieces of social and economic research. Here are a just two of the nuggets from The Second Curve that might have some interesting applications in the NGO sector.

- ” … 93 per cent of all the businesses in Britain are microbusinesses, employing less than five people, often just one person or a couple. In total they only produce 3 per cent of the national GDP but in aggregate they employ more people than the whole of the public sector.” (p66) What if the NGO sector moved in the same direction? Indeed, with the advent of crowd-funded micro-development and large NGOs outsourcing ever-more functions, maybe this is already happening.

- “Zhang Ruimin, the founder and boss [of the huge Haier domestic appliance company in China], started dismantling the corporate hierarchy in 2009 and now has 2,000 self-managed teams. Any employee can generate their own new idea – for a new appliance model or a new feature on an existing model – by examining customer comments and market information. If approved by management that employee can create and manage their own team to implement the project, which will involve persuading specialist staff to contribute their time” (p 133). How might this idea – of creating a confederation of tiny self-organised NGOs under one corporate glass roof – help to stimulate innovation in our larger INGOs?

Charles Handy has been described as “gentle but incisive”, and The Second Curve proves that he can be both provocative and inspiring – a critical friend guided by genuine concern for our future as individuals, communities, organisations and globally.